Book Review IV: A Bend in the River, by V.S. Naipaul

A departure can feel like a desertion, a judgement on the place and people left behind.

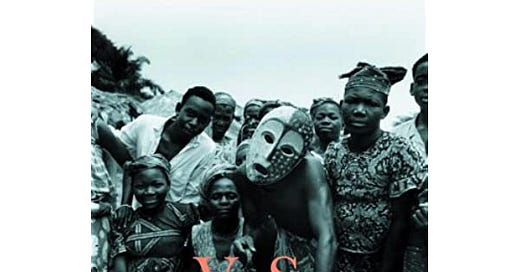

It took me 17 days to finish this book. Far longer than I assumed it would. But, I guess, it just wasn’t what I had expected. It had hit my radar after seeing it on a list of Mike White’s favorite books. (Mike White is the guy who wrote and directed The White Lotus.) Based on that — and on the cover — I expected it to be wilder, darker, more primal. Instead, it was set in the heart of post-colonial Africa in the 1970s. A wild, dark and still primal place and time, for sure, but one with cars and jets and fast food restaurants. Not a bend in the river in the bush surrounded by darkness, but a bend in the river where a city lives, is destroyed, and lives again.

I am not a smart reader. I rarely see past the face value of novels. I don’t see metaphor or symbolism unless I am beaten over the head with them, I don’t pick up on social commentary, or theories on the patriarchy buried in the characters. I love to read. I love reading challenging books. But I don’t see their deeper meanings, even though I know they are there. I don’t even try. Maybe this is why I love the Knausgaard My Struggle series so much. He is asking nothing of his reader but to take his story as he tells it. Which, of course, is its brilliance.

A Bend in the River is far deeper of a commentary on colonialism, Africa, expatriatism (and way more) than I bothered to dive into while reading the book. In that commentary is its meat, its Nobel Prize winning marrow. But I completely ignored it. And so what was left? The story, and the language it was told in. Which is, if the book is well crafted enough, usually more than plenty for me. A Bend in the River, I think, is such a book.

The story takes a while to get moving. It is too episodic to start, but I forgave that I as I read on, as the characters in each episode truly did need a lengthy introduction in order for the rest of the book to work. Around the halfway mark, it starts to really cook. And we, the reader, are — thanks to the language — placed quite firmly in a third world country in the heart of Africa in the 1970s. Its heat, rain, mud, jungle, corruption, poverty, drunkenness. The story moves to London for a short time and that, too, rings true. London in the 1970s; new immigrants in crowded spaces. But then the main character beats his lover (twice) and deals in ivory (for which he goes to jail, for which we are to feel sorry for him?) and so all of a sudden the hero becomes the anti-hero and the story is lost. Until the ending, which is almost perfect.

And, so, the story and the language were enough in this case. Albeit just barely. The book often felt like a slog. But there was such clarity in the writing; sincere and sad and full of life. And the story moved along just fast enough, with just enough moments of piercing and perfect language.

One such moment shows up about halfway through. It is a goodbye. Two goodbyes actually. The chapter on the goodbyes lasts for many pages, which sounds grueling and tedious but was not in the slightest. It was sad but full of hope, in the same way that all goodbyes can be. I recall the goodbye in The Tin Drum which I think about at least once a week and probably will forever. Although that was just one paragraph in an otherwise just-okay book. This was an entire chapter in a much better book. A line that sticks out that I cannot shake (writing of the water hyacinths in the river):

“Now, lilac on bright green, they spoke of something over, other people moving on.”

I have found, over the years, that the stillness in the house after guests leave and you are waving goodbye on your stoop before sinking back into your life is the greatest stillness in life. And Naipaul, in six short words, grabs that stillness by its heart: “something over, other people moving on.”

In the end, I guess, that one line was enough for me. Enough story, enough language.

This is a book I liked far more after finishing it than I did while I was reading it. What that says about me, the author, and the book itself, I am not quite sure.

*

Next up: The Sea, the Sea, by Iris Murdoch